WFP Column: Learning Curve

Landmarks: Learning Curve – Going back to school on the design of education

On the occasion of its 50th anniversary, HTFC Planning & Design is hosting a series of conversations about the landmark plans and places that have shaped our province over the past five decades. The focus will be on pivotal moments, when new ideas altered the course of development and influenced how we see ourselves and our communities. Each article will follow the changing public discourse around these moments over the last half-century, and examine them within the context of the wider social, cultural and political debates of the day to draw lessons for the future.

An Indigenous Circle of Courage dotted with reclaimed ash stumps instead of desks. A raised vegetable garden fed by a lunchtime compost recycling system. A new indoor student commons whose large glass curtain wall connects mirrored indoor and outdoor performance spaces. A rain garden planted with native and adaptive plants. While they may not conjure the image of traditional school grounds, all of these places have replaced blank brick walls at Collège JeanneSauvé. The new learning commons at CJS are designed to educate, restore, and strengthen relationships between the school and the community.

These changes represent an important departure point in the design of schools, which has remained largely unchanged over the past half-century. “Most schools are still based on a one-room schoolhouse model. Classrooms are all lined up next to each other and linked with a corridor,” architect Greg Hasiuk says. “I don’t think school design has fundamentally changed in the last century, whereas the curriculum and the way educators teach has transformed immensely.”

In this edition of Landmarks, we dive into the world of education, and talk with local experts about the past, present and future of the design of learning environments. We brought together Hasiuk, partner and practice leader at Number TEN Architectural Group, the firm that designed Met Collegiate and the new learning commons at Maples, Collège Jean Sauvé and Garden City Collegiate; Monica Giesbrecht, principal at HTFC Planning & Design, and the lead landscape architect for the CJS and Maples commons projects; Matt Henderson, assistant superintendent of curriculum at Seven Oaks School Division, and author of Catch a Fire: Fuelling Inquiry and Passion Through Project-Based Learning; Lise Brown, founder of Momenta, an organization that specializes in outdoor experiential education; and Sheila Grover, cultural historian.

● ● ●

There’s an old industrial model for building schools: view the school building as a “factory for learning,” maximizing the time spent in the classroom while minimizing distraction. “Most often schools built in Manitoba between the 1950’s and the early 2000s were not built with any consideration for the learning potential of their outdoor environments,” says Monica Giesbrecht.

Architect Sim Van der Ryn explains in his book Design for an Empathetic World: “[The head of Van der Ryn’s design firm] told [him] of a study done in window-wall and almost windowless classrooms in which a movie camera recorded the entire day. The team then counted the number of times the children turned their head to look at the outside wall rather than […] the teacher.” The conclusion of the study was that students in the window-wall classroom looked outside far more often than students in the windowless classroom looked at the blank wall. By extension, it was believed that forward-facing students were paying more attention, and the trend toward windowless classrooms and artificial lighting began.

The Indigenous Circle of Courage at Collège Jeanne-Sauvé. Photo: Shannon Loewen.

Window and glass materials were significantly more expensive and less energy efficient in the 1960s and 70s. The extensive double glazing we have in most modern buildings was impossible with the technology of the time. The economic austerity and growing anxiety surrounding the Cold War only intensified the issue, encouraging a more brutalist aesthetic that favoured heavy concrete, brick, or cinder block shells. Often these buildings were turned inward, with classrooms organized around a central corridor or common space, like a library.

“I gave a presentation to teachers in training at the Faculty of Education eight years ago,” says Greg Hasiuk, “where I was talking about the benefits of having a visual connection in the classroom to the outside and the importance of taking a visual break and looking at nature. And I had students say to me ‘isn’t it distracting for students to have windows in the classroom?’”

In fact, studies show that a visual connection to nature can help stimulate healing, mental relaxation and focus. “‘Head forward’ is not a measure of whether a student is paying attention,” Van der Ryn explains in Empathetic World. “The students were not interviewed about their experience in the classroom and their performance was not considered. Subsequent studies showed that windowless classrooms actually depressed student performance, while similar studies in hospitals by Roslyn Lindeim and Roger Barker of the Midwest Psychological Field Station at the University of Kansas showed that patients recovered faster when they had a view to the outside […].”

Giesbrecht agrees. “As landscape architects, our largest collaborative effort with architects is to connect inside and outside. We work closely on projects to ensure that even when students are inside the building they can maintain a strong connection with the surrounding landscape.”

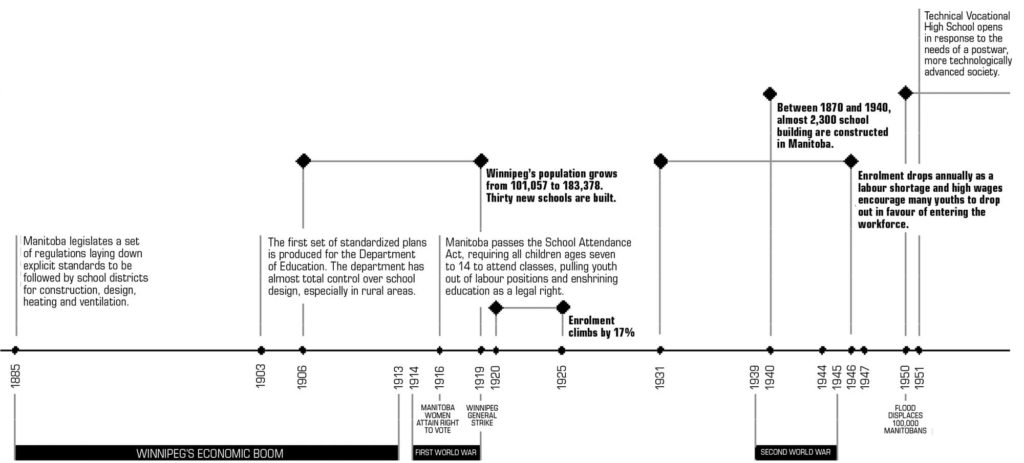

Meanwhile, in the post-war period, there was a shift, but not necessarily in the design of the buildings themselves. The 1950s brought growing numbers of young people, and the result was a rush to build larger schools with more varied curriculums to compensate. “Between 1931 and 1947 enrolment levels in Manitoba schools dropped every single year,” explains Sheila Grover. “So there was this kind of hiatus of investment in schools and curriculum during the depression and World War Two eras, followed by a scramble to reform and modernize in the post-war period with the arrival of the baby boom.”

This new curriculum was about creating citizens of the world in the wake of World War Two, equipping students with the technical skills to participate in the global economy. Schools became larger, but still maintained their industrial, inwardly focused aesthetic. Recreation was becoming more integrated as physical education, recess breaks, and sports teams became more common in the school system and were filled out with Baby Boomers.

“A good example of this shift can be seen if you compare the footprint of a school such as Isbister School on Vaughn, the last remaining 19th century school in downtown Winnipeg, to a school built around World War One such as the old Kelvin High School, to a more contemporary school such as Sturgeon Heights Collegiate,” says Grover. “You go from a postage-stamp size site, to an enormous yard with football fields and running track.”

The last 10 to 15 years have seen another shift.

Matt Henderson explains: “There is an emerging focus on creating ‘educational experiences’ for students, where learning is more engaging and inquiry-driven and where students play a role in the learning process by connecting with experts or undertaking research inside and outside the classroom.”

“What we see today is more of an emphasis on discovery and investigation as opposed to a more didactic approach where the teacher is the one with the answers telling the students what they need to know,” agrees Grover. “Classrooms today are laboratories for young minds to fizz and pop and make discoveries.”

Part of this shift in educational models entails understanding the new skills required for young people entering 21st century society. Technological, collaborative, and interpersonal skills are becoming more and more vital as our civilization becomes more connected. “In our work with schools and school boards we’re seeing a greater shift towards project based learning, more collaboration and team-based teaching,” says Hasiuk. “So we’re trying to break out of the ‘box’ classroom, figuring out what 21st century work skills are and how to create spaces that support them.”

“There is a tendency to want to approach things in order in education, but when we use emergent and inquiry-based learning we can trust that topics, questions and curiosities will emerge, we may not know when or how, there’s a certain amount of trust that is needed, trust in the process and trust in the students excitement to learn,” says Lise Brown of these changes.

Today’s student has changed, too. New technologies and means of communication have created entirely new ways for young people to relate to the world and each other. There are new social pressures, and students may find themselves struggling in mainstream school systems. Learning disabilities and behavioral issues are being increasingly researched and understood, and they often require newer, more flexible solutions than those of the past century.

“People learn in all kinds of different ways, and experience life in different ways. There is a growing body of research that shows that for many kids and teens the traditional classroom is not the best setting for learning, growing and evolving the social and analytical aptitude required to navigate life.” says Giesbrecht.

“[At Momenta], we work with many students and families who are struggling within the mainstream school system in some way,” says Brown. “For example, a parent who has a child with challenging behaviours will reach out to us looking for an alternative to the school environment where their child can learn and build some of these skills in outdoor or therapeutic environments.”

With a greater understanding of all these issues, educators and designers are adapting to furnish new learning environments. Contemporary classrooms may be designed as “labs,” with a focus on experimentation and different functional zones for “wet and dry” or hands-on activities. Or they may be created as “design studios,” where the classrooms themselves become spaces to rethink how learning spaces function.

“Some people will say, ‘you’re just doing open area,’” says Hasiuk of the trend toward more open, airy education spaces, “but we definitely are not. What we’re doing is providing more flexible learning environments for teachers and for kids, and more space for collaboration.” Beyond this, as more teachers embrace project-based learning and new styles of learning environments, students are spending more time outside classroom walls. “Our learning environment is the actual community.”

Nelson MacInytre Collegiate was the first to embrace the project-based model as the standard method of instruction school-wide. Three times a year their “Weeks Without Walls” program releases students into the community to delve into careers and other interests. The Seven Oaks School Division’s MET Collegiate is another example of this new approach. Student learning is self-directed and involves a high level of engagement with the wider communities through field studies and mentors. In 2017, MET students participated in the On the Docks design competition, where experiences were created around the project to give students an opportunity to learn about the Alexander Docks from a variety of perspectives.

Seven Oaks’ Matt Henderson says there is an emerging focus on creating ‘educational experiences’ where learning is more inquiry-driven.

“We curated learning experiences for students leading up to the competition, where students met with contractors to talk about what it means to build on this site structurally and geologically,” says Henderson. “They talked with Elders about the history and cultural significance of that site and what it means to build on Treaty land. They talked with members of the Drag the Red group about missing and murdered Indigenous women. They talked with architects about what it means to design space for people.”

With projects like this, the classroom becomes a kind of “springboard,” where students return to sift through their field research and make connections. “We’re thinking about how to create ‘in-between’ spaces that bridge the classroom and the community,” says Hasiuk. “The idea is to create a home base that gives teachers and students more flexibility to move between spaces and promote different modes of learning and a sense of belonging.”

The way we design outdoor school grounds is also evolving to meet this shift. Outdoor environments provide students with an opportunity for learning that is hands–on and engaging in a way that the classroom is not. A well–designed schoolyard can bridge connections between the community and school.

“Research shows that kids thrive when they are outside and engage with their whole bodies, physically, mentally and emotionally,” says Brown. “To be able to go out on the land and have emergent learning experiences makes them feel like they have achieved something that is incredibly therapeutic and empowering.”

“School grounds are more than just spaces you go for recess to burn off steam three times per day,” Giesbrecht says. “They provide incredible learning opportunities in their own right. Our office thinks of schoolyards as a launching pad for getting students and teachers outside the classroom to experience and investigate wonders and challenges in the real world. We also love the side benefits of fresh air and unplugged human interaction that happens ‘out there’. Taking the step outdoors to inquire and be curious together builds social skills, confidence and empathy eventually leading students further afield into the community with the tools they need to continue their learning journeys.”

Brown agrees that outdoor schoolyard opportunities are important. “Outdoor learning doesn’t just happen in far away forests. Schoolyards are a massively underutilized resource, and are often empty fields. Play structures on school yards become seasonal resources due to winter and spring elements causing surfaces that become a slip hazard. There are other kinds of ways that kids can play and learn and have fun on school grounds if yards are designed differently, with natural elements that peak curiosity and change with the seasons.”

“There is so much learning that can come directly from the land when it is in it’s natural state, through observation and investigation and storytelling. There is no limit; everything from science, mathematics, history and art can be learned in some way through the land.”

Designing outdoor environments to support learning requires a certain amount of flexibility. When it comes to public spaces, the landscape needs to function for the widest number of people possible. The approach requires a focus on creating places that are accessible and multi-layered. “Our approach is really to build a good natural environment that is comfortable for people, with all the amenities and ecological functions in place, so that teachers, if they are so inclined, will take advantage of the learning opportunities available and find novel ways to bring learning outside the classroom,” says Giesbrecht. “We have seen things that I never would have imagined being used outside for teaching math, geometry, social science, history and biology in the spaces we have designed.”

“What we have to be careful about is that we don’t just build outdoor places for a narrow use or view expressed by a single educator, parent or administrator and their needs. We always strive to ensure that the environment is flexible and can accommodate a whole range of unplanned and unexpected needs.”

“It doesn’t take much,” adds Brown. “I’ve done workshops in a patch of bushes at the edge of a school field and have had impactful learning experiences with students and teachers. It goes to show that you don’t necessarily need an expensively designed forest school you might see on the internet, you literally just need a little bit of land and natural habitat.”

Open-air spaces, such as this one at Ecole Sage Creek, are designed to be more flexible learning environments for both teachers and students. Photo: Number TEN

On top of being used as learning environments, school grounds are increasingly playing an important role as community hubs. This is especially true in urban areas where greenspace may be limited. “One of the big changes I’m seeing across North America is instead of investing money into an impressive lobby or entrance space, schools are investing in exterior and interior learning common spaces that provide connection between the school and wider community and promotes a ‘learning happens everywhere mentality’,” says Hasiuk.

Henderson has seen this change in action in the Seven Oaks School Division. “All three of our senior year high schools have very large common areas that have really turned those schools into a community hub,” he says. “If you go at any time of the day, be it a weekend or weekday evening, you see these common spaces packed with community events.”

Seven Oaks is also growing a new land-based education centre that takes outdoor education, stewardship to a new level. The Ozhaawashkwaa Animikii-Bineshi Aki Onji Kinimaagae’ Inun (the Aki Centre), or Blue Thunderbird Land-based Teachings Centre, is a dedicated facility on the northwest edge of Winnipeg. The Aki Centre offers hands-on programming and projects for students from Kindergarten to grade 12.

“Initially we were thinking this would be an agricultural learning centre but very quickly the vision expanded,” Henderson said of the project. “It was discovered that the property contained remnant prairie with numerous species of indigenous plants. So we’ve been working to restore this prairie and turn this into an educational opportunity for students.

“The Aki Centre is different from a Fort Whyte Centre where you can be led along a boardwalk and learn about the different aspects of the environment from interpretive signs. When our teachers bring students to the Aki Centre, the learning happens through direct investigation: what are the bird and plant species that are out here, what is a prairie ecosystem, what was here historically, what has changed and how might things change in the future? So there’s a ton of potential for learners to get involved in learning about everything from climate change, geography, history, social and biological sciences.”

The Aki Centre offers land-based learning.

Giesbrecht, who worked on the project with landscape architects Bruce Dixon and Kaili Brown, explains more about the design: “It is great to hear you talk about that project evolving in real time because we always designed it as a living laboratory, and that is exactly what you are describing. We didn’t know if it would end up being a primarily agricultural site or tall grass prairie so we built the groundwork that could support either. The design shaped the land into a rolling topography with dry areas and wet areas . The entire site uses a whole systems approach with the building designed by Prairie Architects as the hub of the action. As landscape architects we love it when owners embrace the landscape and become the stewards of it’s evolution. It is the best thing about mother earth. She is a constant rejuvinator and educator if you listen to her.”

In some European countries, outdoor education is a long tradition. “Forest schools” are entirely outdoor classrooms that focus on student-led inquiry, and they have their roots in Denmark and Germany in the 1950s and 60s. More recently, they’ve started to become a trend in North America, and several have been established across Canada.

We can see the concept on a smaller scale through programs at Fort Whyte Alive and Momenta. “One of the big principles behind the forest school philosophy is the idea of returning to the same natural area over and over so that kids can build memories of place, see seasonal changes and notice things that can spark learning,” says Brown, who founded Momenta in 2006. “Another principle is that the learning is child-led and inquiry-based, where we allow the child to direct learning around questions or things that interest them in the environment.”

Research has found that outdoor play can help children develop imagination, strengthen self-confidence and social skills, and help in developing their capacity to solve problems, be creative, and grow intellectually. “Parents have commented after our forest school programs – their children’s imaginations start growing more, they are more able to entertain themselves, and often moods start balancing out,. Children are better able to regulate their emotions and are overall just really happy,” says Brown. “In the colder months the kids come home with rosy cheeks and an overall glow of happiness that just permeates.”

Giesbrecht notes that we are starting to see a more mainstream embrace of these ideas. “In Manitoba we had started to see a shift at the Provincial level towards funding for outdoor learning environments in new school developments. While these programs have been cut back in recent years, we are finding that the School Divisions and Parent Councils see the value of nature grounds as play spaces, community hubs, and low impact environmentally responsible places and are coming at us to help them create these types of school grounds. Instead of funding large, single use, cookie cutter play structures that can not be used year round, these groups are investing in holistic neighbourhood places that support all types of play and learning. The best part is that this is happening on both new schools being built now and on older schoolgrounds from all of the school development eras of the last century we discussed earlier.”

Number TEN is focusing on research to better understand the data underpinning how educational spaces perform and function from the perspective of teachers and students. They’re currently working on a project to gather information on how teachers make use of current “traditional” space, to be compared with future data about how they use new learning environments. “It’s a huge change management issue, and designers are having to learn how to talk the lingo and think forward and stay fresh,” says Hasiuk. “We worked with a PhD researcher who helped ensure our language and design philosophy were aligned with the emerging trends in education and to do so in a way that made sense for administrators and decision-makers in the education system.”

“Our office also invests in ongoing research that helps us create increasingly responsive landscapes. We conduct post occupancy visits with schools to see how our outdoor spaces are working several years after opening and participate on national nature playground standards committees for the CSA where emerging best practices across Canada are researched, compiled and shared with the design and construction professions.” says Giesbrecht.

Design alone is not enough to promote new forms of learning. The same can be said for curriculum or teaching methods. “I have worked in state-of-the-art schools with modern flexible classrooms and furniture and everything else, and still see a lot of traditional teaching methods with kids sitting in chairs in rows,” says Henderson. “That’s not to say that’s bad. There is a time and place for lecturing and I use that method, but innovation in the classroom needs to be supported by the actual pedagogy, with teachers who are willing to experiment and with schools and boards willing to support that kind of learning.”

“This is so true,” says Giesbrecht. “We can design and build amazing outdoor environments but it is really how the everyday users of the space, the teachers, students, parents and neighbours adopt and enliven these landscapes throughout the seasons that transforms them into vibrant, useful and meaningful places in their community.”

“There’s a story I like to tell about the grand opening of West Kildonan Collegiate,” says Hasiuk, “where a former alumni of the school, Randy Bachman, gave a talk to students. He said, ‘You know, I dropped out of school when I was in grade 11. I was in a rock and roll band the idea of sitting in a classroom just didn’t fit me. So I spent a lot of time in the parking lot. If there was a space like this when I was going to school—a common with a stage and a town square feeling—I might have finished high school.’ Here’s a guy who is brilliant in so many ways, and he pointed to the physical environment as an essential ingredient for the success of young people in school.