WFP Column: Cultivating Community

Duets: Cultivating community, one garden at a time

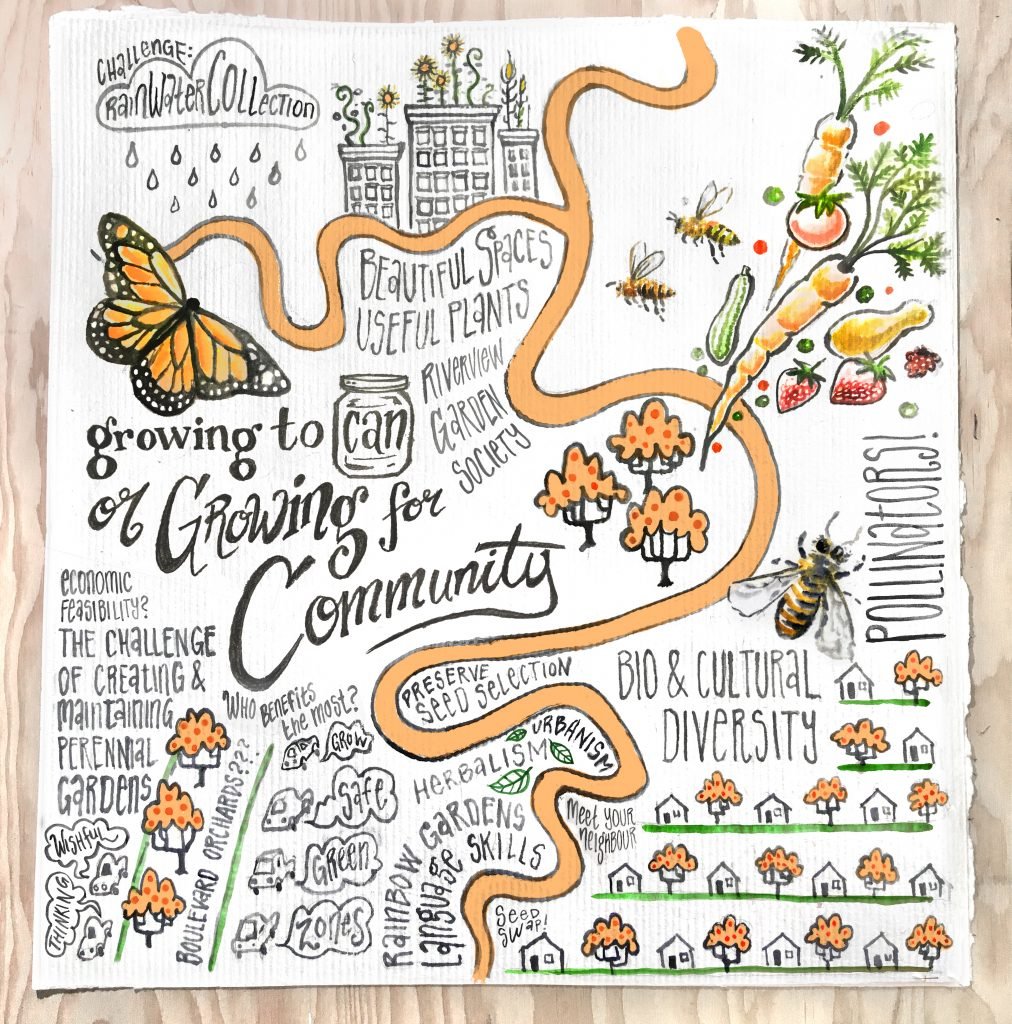

From inspired entrepreneurs full to the brim with ideas for our city to the many pop-up shops that have emerged in our downtown. From the corner coffee shop to the local body shop, design is everywhere. DUETS is an exclusive Winnipeg Free Press series that pairs design experts with local champions and innovators to brainstorm new opportunities for civic building. Interviews by HTFC Planning & Design, written by Kristen Shaw, illustration by Victoria McCrea and photography by Lindsay Reid of CLICK.STUDIO.

Though it’s pushing 30 degrees, there are several gardeners braving the afternoon sun to tend their plots at the Riverview Gardens. Six local garden experts and enthusiasts pick a shady spot under a large willow tree to explore the ins and outs of community gardening.

Maureen Krauss is a principal with HTFC Planning & Design and an avid home gardener. In the late 1990s, while working with FortWhyte Alive, she travelled to Boston to learn about community-shared agriculture (CSA), a model brought back to Winnipeg as a means to introduce urban agriculture to underserved youth. “Starting FortWhyte Farms was a big piece of the sustainability puzzle,” she says. “We were teaching environmental education, but we also wanted to embark into social enterprise.”

Ryan Pengelly splits his time between farming on a mixed farm with his family and being a community planner with HTFC, working in rural and northern locales with Indigenous communities on large-scale development projects. Currently, he grows quinoa and other grains, selling at various farmers markets and directly to restaurants around the city.

Nik Friesen-Hughes became interested in gardening while studying Greenspace Management at Red River College and Urban Environments at the University of Winnipeg. He’s been a volunteer with the Sustainable South Osborne Community Co-op People Garden for the past five years. He gardened with Urban Eatin’ Landscapes for the past three years as a designer and contractor, and now consults on and designs gardens independently with Shannon Bahuaud.

Bahuaud says she’s always gardened, starting in her family’s garden when she was a child. “I ended up studying herbalism and did an internship at a medicinal herb farm in Oregon in 2012,” she says. “When I came back I started working at St. Norbert Arts Centre and got really into doing landscaping and gardening.” After going to Ontario to run an organic CSA for a year, she came back to Winnipeg and began working as a garden consultant and designer.

Maureen Krauss, Ryan Pengelly, Nik Friesen-Hughes, Shannon Bahuaud, Rob Moquin, Rodney Penner and Kristen Shaw gathered at Riverview Gardens to discuss issues such as food sovereignty and sustainability. (LINDSAY REID PHOTOS / CLICK.STUDIO)

Rob Moquin is the vice-chairman of the Winnipeg Food Council and policy manager of Food Matters Manitoba. “I’m just passionate about all things food,” he says, explaining that he has a diploma in culinary arts, an undergraduate degree in human geography, studying urban food systems, and a master’s degree in natural resources management. He has researched community building through gardening initiatives in Kenora, and now works looking at food security policy in Manitoba.

Rodney Penner is the City of Winnipeg’s naturalist. He oversees the naturalist services branch, which helps co-ordinate community gardens across the city. The branch also takes care of many other naturalist services — from riverbanks to natural areas to butterfly gardens at schools.

Techniques and models of community gardening are continuously evolving. Surrounded on all sides by the productivity and diversity of Riverview Gardens, these experts explored issues from food sovereignty and sustainability to fostering community and education.

Why are community gardens important?

• Bahuaud: The first thing that popped into my head is The Forks orchard: I’ve had lovely conversations with strangers picking raspberries there. It’s much more in the public sphere than having your own plot. You gain that sense of community. Also, having food sovereignty is really important. Being able to pick and choose what you’re growing, being able to seed-save and collect your own seeds, making sure you have organic or heirloom… you have more control over what you’re growing. It’s inspiring to other people, too. I see people say, “Oh, you’re growing this, maybe I want to try that out.” There’s that sharing aspect, trading seeds and information. We’ve also done some work at the Rainbow Community Gardens. (Rainbow is operated by the Immigrants Integration and Farming Community Co-op.) Going there was really interesting. There were vegetables I’d never even seen before! It was a really neat place.

• Moquin: Food Matters Manitoba helped to initiate the Rainbow Gardens. We’re a little bit more hands-off now, but we are supportive. It’s a large newcomer garden on property at the University of Manitoba. It’s famous for what we call world crops. The idea is that there’s new and emerging foods that people like to eat — for newcomers especially, but for others, too. Sometimes the hardest things to access are traditional, cultural foods.

• Krauss: What would be an example?

• Moquin: All sorts of things! Linga linga, which is related to amaranth. Varieties of beans, melons and leafy greens. We also find a lot of cross-cultural learning in those spaces. For example: amaranth. Some people use the seed and some people use the leaf. Learning from each other about the different uses helps to maximize the use of that produce.

Nik Friesen-Hughes (left), designs and consults on gardens and Ryan Pengelly is a farmer and community planner with HTFC.

How does community gardening add to the sustainability of a city?•

• Friesen-Hughes: We have to look at our agriculture system and the elements of it that aren’t sustainable. Community gardening contributes to different elements sustainability. You can learn how to garden. You can build community. It’s also more sustainable using urban space to grow food instead of growing it outside the city and spending fossil fuels to bring it in and package it up. It’s higher-quality food that you’re growing. There is great potential when you start talking about using rooftops and greenhouses and community spaces, and using our current urban spaces, more efficiently. There’s also increased biodiversity in these gardens that we all benefit from.

• Pengelly: I drove in three hours today to Winnipeg, and there were four crops being grown that whole distance: corn, canola, wheat and soy. And you walk in here (to the Riverview Gardens), and it’s a hundredfold, the biodiversity. This is a really unique space that just doesn’t exist in the rural areas. Agriculture is corporate-dominated and export-dominated. A lot of those crops outside of the city are going elsewhere, and this is much closer to sustainability than what you find outside of the city.

• Bahuaud: I also find community gardens can also help lower-income people. It can really help put a dent in your food bills. It increases quality of life to be able to grow better foods. It’s cheaper.

• Krauss: It is time-consuming, though! Sometimes, it’s a hard balance for people who are trying to work. I know the time that it takes to tend a small plot.

• Bahuaud: That’s true. There are tricks to save on time: with mulching techniques or collecting your water at the rain barrel. That’s where the community aspect can come in and you can learn so much from each other. It creates a hub for learning. You can help people out.

• Friesen-Hughes: I do think different kinds of community gardens can be more efficient, as well. In some of the gardens we have that are more communal, if you can’t water for a week or two, someone else can manage it. You can all work together. There is greater support for maintenance and an opportunity to learn.

What kinds of community garden are there? What are the differences in how they’re run?

• Penner: There are a lot of different types of community gardens out there: from the food-production end all the way to butterfly gardening and gardening native species for the sake of habitat. Your basic form of gardening would be the allotment plots — and some community gardens are also set up this way – where individuals rent a plot either from the city or from a community group. Plot sizes vary. Some of them are raised-bed containers all the way up to plots that are 100 feet by 50 feet. It takes a pretty serious gardener to handle those plots. And then you’ve got community gardens where individuals work together and produce food together. We’ve also got school groups out there who are doing butterfly gardens. Church groups are doing habitat gardening along some of our greenways. It’s really varied. Some of them heavily rely on community while others are much more independent.

Rob Moquin is vice-chairman of the Winnipeg Food Council and policy manager of Food Matters Manitoba.

• Krauss: Is there enough to meet the demand?

• Penner: In some areas, we have more people interested in gardening than what we have garden plots for. In other areas, we set up gardens and we have trouble finding people to garden them. It really depends on the community. A lot of people don’t want to have to travel very far to get to their garden plot. You don’t want to have to travel for half an hour or an hour to get to your garden plot. In communities where you’ve got a lot of single-family residential houses, garden plots don’t necessarily go that fast.•

• Krauss: They’ve got enough space in their own backyard.

• Penner: Then you’ve got some areas where there’s more demand than space. There are different types of people who are gardening: some people want the big allotment plot where they can try to grow a lot of food for themselves, and maybe do some canning. Then you’ve got other people who want more of the community experience. They’re not as concerned about the size of their plot, they just want to be able to garden amongst others and maybe grow an international crop or something that’s a little more unusual.

What are the rules in Winnipeg around what you can do with produce you grow? Can it be sold?

• Moquin: There’s a report being tabled by the Winnipeg Food Council making recommendations for expanding small-scale commercial agriculture in Winnipeg. It covers redefining principal use for residential land. Currently, community gardens are allowed as a principal use on residential plots, but agriculture isn’t. For instance, if you owned a lot that didn’t have anything else on it, you couldn’t just grow yourself a fruit or vegetable garden. We’re looking to change that, and also the rules around what can be sold. We’re looking at selling produce grown on city-owned land and the potential to grow things on public land, using boulevards and potentially parkland. It’s great for sustainability for some of the gardens.

• Penner: It’s a good thing, because some policies are lacking, and there are so many differences between private land, public land, the different jurisdictions within public land… there are different agreements as far as leases, rentals and all sorts of things.

Maureen Krauss (left), is a principal with HTFC Planning & Design and an avid home gardener, and Rodney Penner is a naturalist with the City of Winnipeg.

• Krauss: So this will help sort some of this out.

• Pengelly: It seems like there’s a ton of space across the city in boulevards and right-of-ways that could be utilized, not necessarily for gardens, but more fruit trees, permaculture.

What’s the current status of that and where could it go?

• Moquin: From what I understand, growing any sort of produce on something like a boulevard is not permitted. This would be opening that up. The major concern is food safety. There are guidelines in other cities that Winnipeg is looking to. I think the province even has some guidelines around that. Another concern is sightlines and how high crops can grow or the lower canopy of fruit trees. It looks promising that growing stuff on the boulevards will happen in the future, but what, and under what conditions, and using what guidelines, is still up for discussion.

• Krauss: It’s not that easy and straightforward when you think about it.

• Penner: It’s a challenge, too, because the soil in the boulevard area…

• Krauss: … is the worst with our winter salt!

• Penner: It’s pretty bad stuff. If you want to try and grow a tree on a boulevard, you’re talking about bringing in a lot of soil. It’s also the transmission line for a lot of the services that we have. You have water lines, telecommunication cables, all kinds of things that are underground. So if you look at all the boulevard areas in the city, it doesn’t mean that all of them are going to be available.

• Friesen-Hughes: I do think, as amazing as green roofs are, and I do see them as part of the future, we have to use the current space we have more efficiently. We have Kentucky bluegrass growing everywhere, and it’s a relatively recent idea that that’s beautiful and desirable. With the exception of sports fields, I don’t really feel like anywhere in the city should even have grass. I think it should all be food or prairie plants. Long-term prairie plants are more sustainable, they require less water and are drought-resistant, require less maintenance, less fertilizer, and can be productive by providing habitat, retaining water and nutrient runoff, cleaning air and cooling cities more so than a boulevard of turfgrass.

• Bahuaud: Near Park Boulevard West and East, just off Grant and Corydon, there’s this giant field of nothing. Just grass. It’s not a soccer field, it’s not a sports area. It’s just a few trees, and every time, I think, “Why is there not something here?” It probably wouldn’t be a good place for a community garden, because everyone has such big yards in that area, but maybe an orchard or something. Every time I drive by, I think, “I want to work on this field! I want to do something here!”

Are empty lots viable spaces for long-term community gardening?

• Penner: They’re difficult. You’ve got some that are really useful as community gardens, as a place where people can garden for community and some of the intrinsic values of gardening, more so than for the amount of food. A lot of times you have to do raised beds, so there’s all kinds of issues if you have small, inner-city lots. There are shade issues, tree-root issues, the soil is almost definitely inappropriate — there’s a lot of clay. If you’ve got small plots, you have to have individuals or groups who are really bought in, otherwise things don’t necessarily take so well.

What are some ideas for incentives that the City of Winnipeg could offer for community gardening?

• Moquin: I think it would be good to incentivize something like surface parking lots. I think those conversions are slightly easier than some of the older buildings, which I think would be quite costly. Incentivizing portable, container-type gardening on some of these surface plots would be a plus.

• Bahuaud: I find a really good incentive for me, and something that’s been a barrier, is access to water. If there was some kind of system to have water-collection devices, or water delivery, it would really take a huge barrier away from growing. Another incentive would be that, because I’ve always wanted to grow more perennials, and because I do grow medicinal plants, I’d like a plot that I know I can return to year after year and my perennial plants will be there and everything will be the same.

• Krauss: Kind of like a long-term lease.

At the city, every year do you have to put your name in to go back to the same plot?

• Penner: We give gardeners who have had a plot for a year the first right of refusal for their plot. We give them up to a certain date to return to their plot, and if they decide not to return, it becomes first-come first-served. So there is opportunity to make soil amendments or try to improve your plot for future use.

What are some of the values outside of food production that can be found in community gardens?

• Bahuaud: The sharing of gardening knowledge. There are a lot of little things that can be very helpful for someone new to gardening. It would be interesting developing a garden startup package or program where maybe you get a few seeds and information on certain factors to take into consideration. We were talking about how some plots are clay soil — I remember someone telling me that in the ’50s, new homes grew potatoes in their front yard before they put a lawn in, to break up the clay. That’s a great prep crop. There are ways of growing to get your soil to a better point so you can grow more.

Allowing boulevards to be used as gardens face regulatory issues, plus the ground is lacking in quality, say Penner (left) and Moquin.

• Friesen-Hughes: The best way to learn is by spending time in a garden with other gardeners. I’ve learned so much like that. Everybody knows something different.

• Krauss: Back to the Rainbow Gardens, I bet there’s an element of language skills learned there.

• Moquin: Absolutely. Just being in a new place together and co-learning about things outside of just growing, about life in general. I’ve found through my research and my work that a lot of learning is informal. It’s not necessarily workshops that are planned, it’s people just connecting. Another thing that I’ve found is that community gardening doesn’t necessarily have to be in public spaces. I think people community-garden all the time, even if it’s across the fences of their yards.

• Krauss: Dividing perennials and sharing them with friends.

• Moquin: “I had extra seedlings,” or, “My friends organized a seedling swap.” That’s community gardening, even if they’re planting in their own yards. Thinking beyond the space of a community garden, thinking about the community.

Are there gardening events throughout the year, after the harvest is done?

• Bahuaud: I find February is the starting time when you’re thinking about seeds to start in March. There are events like Seedy Saturday at the Canadian Mennonite University.

• Krauss: It’s just at the perfect time of year! In March, there’s this glimmer of hope that you can get going!

• Bahuaud: Having those kinds of community events in the city I think is really, really great. Everyone’s documented what their seeds are. It’s really cool. You find really unique types of seeds. Like the gete-okosomin squash, that’s been around for hundreds of years.

• Friesen-Hughes: People thought it was lost for a long while.

• Moquin: It’s been around.

• Bahuaud: It’s just resurfacing in the general gardening community. It’s so interesting to come across different things like that at a community event.

• Friesen-Hughes: There’s a great gardening community here in Winnipeg.

Maureen Krauss, Ryan Pengelly, Nik Friesen-Hughes, Shannon Bahuaud, Rob Moquin, Rodney Penner and Kristen Shaw discuss fostering community and education.

Want to duet with us? Email HTFC Planning & Design at info@htfc.mb.ca. For more information on your nearest community garden, visit urbaneatin.com.